|

My parents have little appreciation for cartoons. My kids and I, however, enjoy them. My mother tells me her father called all cartoons Cats. “That’s just Cats, he’d say.”

“Why?” I ask. “You know, because of the old Tom and Jerry, and Sylvester and Tweety Bird.” “Oh, I adore Tweety Bird,” I say. Recently we were looking for something appropriate on television for our five-year-old granddaughter Frankie. We clicked on Tom and Jerry. I know some people may complain those old cartoons are too violent. But, within moments, Frankie was laughing so hard we let her rip through the entire series over the next few days. When it ended, she said, “Let’s go back to the first one.” So, we did. I loved my grandfather, Pa, but I have to challenge his taste in some matters. Not, of course, in whom he chose to love—myself, in particular. Has anyone else ever loved me quite so unconditionally? I’ve always loved dogs, as well as cats. My most recent pets have been cats, largely because they are easier to tend if you travel a lot. Over the years, my husband and I have had three cats. They were all gray rescues, but each was unique in temperament. Each was special. Buster was the most loving around humans, though she could be mean to our other cat, who was growing old. “That’s totally natural,” my husband, a veterinarian, said. When Buster died, we did not get another cat. We were travelling more by then. “It’s really not fair to them,” my husband said. “We have to leave them so often.” As different as they were in temperament, one thing they had in common. They all hated to travel. My son-in-law loves cats too, so he, my daughter, and their two kids adopted a pair. Honey and Sunny do not like me, which both surprised and saddened me, especially now that our cats have passed. This does not prevent me from enjoying their antics. I suppose cats are like people. Not everyone is going to love us, even in our own families. This should not keep us from loving them. As a writer, I realize not everyone will appreciate my books. That should not prevent me, or anyone so inclined, from continuing to write and seek an audience for their work. I also love theater, including musicals, and I enjoy the poems of T. S. Eliot. So, I was astonished when I saw Cats in New York and failed to appreciate it. I admire Andrew Lloyd Weber’s body of work, and Memory is one of my favorite songs of all time. Still, it did not suffice to sustain me through over two hours of cavorting humans pretending to be cats. Perhaps I was jet lagged. I remember being tired. In one of my novels (Scorned, unpublished as yet), I resorted to having my least likable character kick a cat. I’ve always considered rescuing a kitten or kicking a cat a cheap device to make the reader like or dislike a character. But, at the time, it felt like something he would do. Actually, he felt so real to me I believed he did kick that cat in a moment of frustration. Later, when he cheated on his wife and she left him, I felt little or no sympathy for the man. After all, he’s also a cat kicker.

0 Comments

June 2024

A Moment in Time Two things grabbed my attention yesterday in the space of a moment. We had just landed in Las Vegas from Maui en route to Los Angeles, and turned on our phones. A text came through from our daughter-in-law, Sarah Hagan. The image of our son holding an Emmy popped into view on my husband’s phone. He showed it to me, and I squealed in delight. I knew he’d been nominated as best director for a documentary, but I’d barely dared to hope. I glanced at Facebook on my own phone, and another image appeared. My first boyfriend—I’d rarely thought of him as such until this moment—had died. David Boaz had teased me mercilessly from the time we moved from Lone Oak to Mayfield when I was eight. It was my Uncle Prentice (he too died recently, only a few weeks before David) who said, “Mark my words. They will end up dating.” I hated David, or so I thought. We were often the last two left in a spelling bee, and invariably I was the one who messed up first. When we graduated from high school, his GPA was a smidgen of a fraction higher than mine. Hence, he made the valedictory speech; mine, as salutatorian, was far less brilliant, less intellectual, less impressive. We also rivalled each other in our ineptitude for sports. It did not occur to me at the time that this lacking might have been more humiliating for him than for me. Always he seemed so confident, so self-assured, so cocky. In fourth grade, I discovered my passion for theater. The two sections of fourth grade at Longfellow were jointly performing “Snow White and the Seven Basic Food Groups.” Yes, there were seven back then. Snow White was cast from the other section, the wicked step-mother (a witch) from ours. The final decision came down to me and Sarah Pierce. “She should get it.” David pointed to me. “She won’t need to wear a mask. Or a fake nose.” He remarked on the length of my nose so often, I spent hours staring at it in the mirror, pushing the tip upward. I resolved to get it fixed as soon as I moved away from home. “Do you know the longest word in the dictionary?” he asked me once. “Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious,” I ventured. He roared with laughter. “That’s not a real word. It’s antidisestablishmentarianism.” Oh, I hated to be bested. He tried to run over me on his bike. Certain he’d swerve at the last minute, I held my ground. But his lack of athleticism prevailed, and he narrowly missed when I darted out of range. Or, perhaps once more, I’d been bested. “Pretend the ball is David Boaz’s head,” the team captain would tell me in kick ball. Yes, our animosity was well known. Looking back, I believe he liked me all along. He had not figured out his sexuality yet. Despite his advanced vocabulary, he likely did not understand what it entailed, any more than I did at the time. He relished our rivalry. Perhaps, despite my protests, I did as well. How thrilled I was on the rare occasions when I beat him in a spelling bee, or in a blackboard race to finish a math problem! When we finally began to date, it was David who made the overture. Despite Uncle Prentice’s prediction, I was shocked. “What??” “I said, would you like to go out sometime?” David mumbled, his face red, his voice uncharacteristically low and muffled. “No way!” But he persisted, and eventually I agreed. We talked, we debated, we argued, we laughed. Oh, we were still rivals, but we had fun. One night I expressed a craving for Boston cream pie, and he managed to locate one. I think of him whenever I see Boston cream pie on a menu, not so often anymore. Tiramisu reminds me of Boston cream pie somehow, and hence of David. Another night, after watching a movie, he remarked, “That actress reminds me of Camille King.” “Really?” I lifted my eyebrows as the green bubble of envy exploded in my veins. “I don’t think so…I thought she was really pretty.” “So?” David was right, of course. Camille was pretty, and I knew she and David were friends. When the rumors began that David was queer, I refused to believe them. Back then, no one I knew ever admitted to homosexual inclinations. There were “sissies,” of course, but I saw this attribute as having nothing to do with sexuality. David was not a sissy, however. He was handsome, if a bit preppy for my taste, well built, and carried himself with excellent posture, even pizzazz. When he never attempted to kiss me, even on prom night, I regarded this as a failing on my part. Undoubtedly, I lacked sex appeal to such a degree the one person who “liked” me could not bring himself to make a pass. I was, once more, humiliated. How he must have suffered, I realize now. We lost touch after graduation. He went to Vanderbilt, while I settled for the nearby state university. I started dating Norm my freshman year, and we had a date scheduled the last time I remember talking to David. We were on break from classes, both of us home for the summer. “David Boaz is downstairs to see you,” my mother called. She always regarded David as the perfect prospect. I groaned loudly enough for David to hear. Reluctantly, I came down the carpeted steps into the living room. “Why are you here?” I demanded. “No reason, apparently,” David snapped. “I guess I’ll be going.” He spun on the heel of his well-polished shoe. “Wait,” I said. “How are you? How’s Vanderbilt?” “Fine. And you?” His tone was clipped. “Fine.” I let him leave shortly after that, without ever learning what he’d intended to say or ask. For some bizarre reason, I realize I’d taken David’s homosexual leanings as a personal insult. How ignorant I was. Another opportunity arose when my husband and I attended a high school reunion several years later. Once again, I blew it. I did not speak to David. Why not? How I wish I had. He was surrounded by our former classmates, and I try to tell myself that he was too busy for me. But I know better. More than once, I caught him glancing in our direction. I went to a few reunions after that one, but David did not. He had achieved national fame by then. Still, I should have reached out. I wish I had. In his obituary, I read that he had a partner for the last thirty years. I hope he found happiness. I believe he did. He had such a zeal for ideas, for interaction… for life. Standing in line at the library in Gulf Shores, Alabama, a few years ago, I fell into conversation with the man in front of me. He was researching medical facilities in the area—and medical errors in particular—with somewhat alarming findings. “Where would you go if you had a medical emergency around here?” I asked.

“Gulf Breeze, Florida,” he said. I made a note of this in my journal, though I’d never heard of the place at the time. That was back before I started having trouble with my right knee and left hip. Recently, I’ve made several trips to Gulf Breeze to see specialists in sports medicine. I think back to my long-ago decision to switch majors from pre-medicine to business. I was convinced I wouldn’t be a good physician, and I didn’t want to be responsible for any failings in that department. Now, having experienced medical errors up close and personal for several family members, I no longer believe I’d have been the worst physician ever. I would have done my best, and perhaps that’s all any of them can do. No one’s perfect, and they are often over-worked. Still… When my mom became unable to keep any food in her stomach, the doctor performing the colonoscopy said, “I couldn’t get all the way. She’s got a really long colon. But what I saw looked fine.” When I kept calling his office, I was told, “There’s nothing more we can do for her.” My mom is as stubborn as they come, and she has long held to a philosophy that doctors are more likely to kill you than help you. Finally, though, she agreed to being taken to the Emergency Room at Vanderbilt. After several hours of waiting and testing, a doctor told us, “We’ve found the problem. There’s a total blockage in her colon where it attaches to the small intestine. We need to operate right away.” After the surgery, the surgeon told me, “I’ve got good news and bad news.” I nearly passed out, so fearful was I of the bad news. “The tumor was malignant,” he said, “but I got it all.” Oh, the relief! It had not spread. A few years earlier, my dad started having chest pains. The attacks—or spells, as we called them—were so violent he’d turn pale and stagger. Often, he’d wake up in the night to one of these attacks. We took him to numerous doctors, including cardiologists, all of whom assured us the problem was not his heart. “If it were his heart, he’d be dead by now,” one cardiologist said. A catheterization was not warranted, they insisted, as the risks were too great. But the spells continued…and worsened. Finally, without an appointment, I took him to the Mayo Clinic to get to the bottom of the problem. We spent over a week seeing various doctors, sitting in waiting room, and listening to medical jargon. They sent us to the psychiatric department in case he had imagined the problem. In the urology department, a young resident found a cancer cell in his prostate and recommended surgery. “Side effects are extremely rare,” he said. We left the Mayo with my dad suffering virtually every side effect and the mystery of the spells unresolved. By this time, he’d had several stress tests, all of which he managed to pass… hence, no heart cath. Eventually, after several years of suffering, he would fail a stress test. The heart cath would reveal that he’d had at least one major heart attack, resulting in damage to about one-third of his heart tissue, and urgently needed a quadruple bypass. Whereas both of my parents’ misdiagnoses ended happily, my grandfather was less fortunate. The state of medicine at the time—and even now—was such that pancreatic cancer was extremely difficult to diagnose and treat. My grandfather knew something was seriously wrong but kept hoping he was mistaken. When doctor after doctor failed to find any source for his stomach pains, he’d feel blessed relief. For a time. But, of course, the pain persisted, and an exploratory surgery finally revealed the cause…after it had spread throughout his system. I could go on. I experienced a botched D and C following a miscarriage that I’ll never forget. My grandmother had a rare illness that, treated too long with steroids, led to a hunched back. But that’s enough for now. Of these maladies, I’ve only addressed one thus far in my books in any depth (The Bell City Bottom, Parts I and II, forthcoming). We all know life is brief, sorrow is unavoidable, and we count ourselves blessed to partake of the glories of existence on earth as long as we do. When I was in high school, Mrs. Ford, my favorite teacher, stopped me in the hall one day. “There’s a great summer job,” she said, “and they asked me for a recommendation. I thought of you at once.”

Because Mrs. Ford taught English, my hopes soared. Editing a book? Writing for a newspaper? I waited for her to explain. “It’s working for Dr. Bennett as a dental hygienist’s assistant. It might even lead to a career as a hygienist yourself.” Ooohh! Putting my hands into stranger’s mouths, smelling their bad breath! Although I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life, I was pretty sure that wasn’t it. “You don’t have to decide right now,” Mrs. Ford said. “Think it over, and talk to your parents. You can tell me tomorrow.” Although I wanted to tell her right then, I agreed to wait. Maybe I wouldn’t even tell my parents. Before I could decide, Mrs. Ford called my mother herself. “That’s a great opportunity,” my mother said to me. “You should definitely go for the interview.” My dad agreed, so I went. My reticence must have shone though my pretense at being interested, so—to my relief—I did not hand the job. Years later I feared the same thing might happen when I interviewed for accounting positions, having chosen that major for two main reasons: (1) I wanted to help put my fiancé through veterinary school, and (2) You could be fairly assured of landing a job after only four years (4.5 in my case, since I’d switched majors) of college. I was not wrong. My reticence did seep through, or I was found otherwise lacking, and several CPA firms rejected me before I landed a job. When I finally put my acting skills, such as they were, to use, I got a job. Nonetheless, I approached my first day with a lot of nervous fear of failure. I liked my colleagues though, and they soon taught me what I needed to survive. Often, after someone on a plane asked what I did for a living, they’d remark, “Oh, I hate math,” or “Oh, I’m terrible at math,” or “I’m no good with numbers.” My usual reply was “Me too,” or “Same here.” This always served to draw inquisitive looks. If I happened to be in the mood for conversation, it worked as an ice breaker. “Accounting really isn’t so much about numbers,” I’d say. “It’s about people.” “How so?” “Your clients need help getting their business off the ground, or getting out of the red (loss) zone and into the black. The numbers are just one of the tools to help get them there. And you meet a lot of nice people, and some really needy ones too.” My mood would darken when I remembered one client in particular. He and his brother had inherited their business from their dad. Every month my firm would generate a P and L (profit and loss) statement for them. “If it’s bad news,” he’d say, “I’m going to relocate to a Caribbean island.” On bad days, he’d say worse. I heard, a few years, after I left the firm, that he shot himself. I wish he’d gone to an island. Thankfully, there were more success stories than failures at our firm. When I did tax returns for clients making ten times my income, they’d whine, “I can’t believe what you’re telling me I owe. Are you sure you can’t find a few more deductions?” I’d vow silently, If I’m ever in a position to make that kind of money, I must remember not to whine about taxes. I would sympathize with the client, employing my acting skills once more to hide my lack of real sympathy. “I’ll try.” Occasionally, I’d find a client who, though losing money this year, was able to get a nice refund by carrying the loss back a few years. This put a smile on both our faces. “What do you do for a living?” I’d ask the stranger on the airplane, and we’d launch into a discussion. Odds were that I’d know a bit about their industry, having encountered such a variety as an accountant. We all know people who seem to know from a very early age what they want to do with their lives. I envy that. I really do.

For example, one of my daughter’s friends from church knew she wanted to be a doctor. She did not get accepted the first time she applied to medical school, or the second. But she persisted, and now she’s a doctor. My daughter, my son, and I were all blessed with a talent for being good at school stuff. We enjoyed learning, we made good grades, and we were evenly balanced between the analytical subjects like math and science and the creative disciplines like literature and art. Unfortunately, none of us knew what we wanted to be when we grew up. I used to tell the students in my graduate classes at Vanderbilt, “Don’t worry if you don’t know exactly what kind of job you want. I’m still trying to figure it out for myself.” They always laughed. They didn’t know I was not joking. Is it ever too late to find your passion? True, it may come earlier, easier, and more clearly to some than others. But I’ve always refused to quit looking. Am I destined to be a writer, an actress, or a teacher? Should my son be an engineer or a filmmaker? Should my daughter be a professional student or a stay-at-home mom? I think back, back, back to my graduation from high school. My parents and I are having a rare serious conversation about my future. It’s already been determined that I will attend the state university that’s only twenty miles from our hometown and much cheaper than any of the alternatives I’ve pushed for. I will be the first college student in our family, and none of us knows a thing about schools’ reputations or how they might impact one’s future. “What are you going to study?” my dad says, spearing his last bite of pork chop. He’s usually the last one to finish a meal. My mother hasn’t leapt up to clear the table before we stop eating as she often does. “I don’t know,” I say. “A little of this, a little of that, I guess.” “No. What I mean is… what are you going to study to be?” “Oh. Like my major,” I say. “I don’t know. Maybe theater.” “Theater?” Mama’s eyebrows lift in astonishment. “What in the world would you do with theater?” They both know I love to be in school plays. I always have, and often got a good part. I think they appreciate my talent. “I could be an actress… or something.” “Maybe.” Daddy frowns. “You have to have lots of connections to make it in that industry.” Mama says this as though she’s done thorough research on the subject. Did Mama, who looks like Vivien Leigh and sings like Doris Day, once entertain dreams of her own? Even if she did, she has no right to quash mine. “Not everybody’s connected,” I protest. Don’t they believe in me? They wear matching frowns now. Maybe I’m not that talented after all. “English literature then,” I say, thinking of the other times, when I didn’t get the role I wanted—even in our little community. “What would you do with that?” This time it’s Daddy who asks. “I don’t know. Write, or teach.” I slump in my chair. My mother picks a piece of lint off my shoulder. “For God’s sake, straighten your shoulders. How many times do I have to tell you how important your posture is?” For what? My mother has excellent posture (which is kind of sad because she develops osteoporosis, arthritis, and a crooked spine later, and will eventually walk as though one leg is longer than the other). “May I be excused?” I push my chair back. “You may not,” Mama says. Her nose twitches just a little, which happens when she’s stressed. But I can’t think about that now. “What do you two want me to be?” I demand. Mama says nothing. Daddy clears his throat. “Whatever you want to be,” Daddy says at last. “You could be anything, do anything.” Except an actor or a writer, apparently. I wait. “Well, now, you could be a doctor, for instance,” Daddy says. A doctor? “What kind of a doctor?” For I know there are other kinds of doctors besides medical ones. There are doctors of philosophy, and occasionally there would be a teacher in our high school said to have a doctorate. And I suppose all the professors in colleges probably have doctorates. Is it possible I might become that kind of doctor? “A regular doctor. Like Dr. Jones.” Dr. Jones was our family doctor for a long time. I think he delivered me. Daddy has eaten everything on his plate, and finished what was on Mama’s. Still he picks up his fork and mashes the remnants of beans with it, which tells me he’s nervous about this conversation too. “I don’t think they offer that at Murray State.” There’s a note of triumph in my voice. “Pre-medicine then,” Daddy says. “Why?” This whole conversation is pretty astounding. I remember when Mama wanted me to take a summer job as a dental hygienist’s assistant. Cleaning people’s teeth seemed to be the height of their ambition for me. “Because you’re so smart,” Daddy says. “If you were going to be a writer or an actress, why would you even need to go to college?” Mama chimes in. “Fine! So now you don’t want me to go to college!” “Of course, we do. You realize you’d be the first college graduate in our family. Ever.” Daddy rubs his temple. “We want that to mean something.” “So do I, Daddy. But what would I do with pre-med?” “Medical school, obviously.” Does he really think they could afford to send me however many years it takes to finish medical school, internships, and whatever else goes with that career path? Apparently so. “But that would take, like, a thousand years,” I protest. Daddy leans forward in his chair, his eyes intent on my face. “And you could help people.” Now it clicks. Being a doctor has often been voiced in my family as the highest ambition. Doctors are, like, next to God. If we’d had one in the family, maybe my grandfathers wouldn’t have died so young. That’s what he thinks. I’m a little flattered, but I can’t honestly imagine myself as a medical doctor. It is only now, all these years later, that I fully realize what a tremendous gift their assumptions were. That I could and should attend college at all, that I would earn a degree, that I might even attend and complete graduate school once or twice. All these things that they had never done and which I, eventually, did. Along the way, regardless of my major, I would be free to study art and theater and literature, as well as science and mathematics and history. Nor did they force a major upon me. They never protested when I switched majors to business, and I doubt they would have withdrawn support if I’d switched instead to art or theater or literature. They were merely offering their opinions. I was free to choose, even if it didn’t feel that way at the time. My mom rises then and begins to scrape the plates. I’m not sure what she thinks about my dad’s ambition for me. I start out as an “Undecided” major. But when I need to choose a major, I do, in fact—for lack of conviction in another direction—declare it as pre-med. It takes me two and a half years to acknowledge, as I’ve suspected all along, I really don’t want to be a medical doctor. I get squeamish around blood, even on a filmstrip, and the thought of medical school terrifies me. By then, I’ve met Norm, who is studying wildlife biology. Junior year, we’re taking Comparative Anatomy. Our professor, Dr. Smith, has a crippled right arm. The rumor is that he was headed for a career as a surgeon before the accident. Maybe he’s a little bitter, or maybe he just wants us to be prepared. Comparative Anatomy is, quite simply, the most challenging course I’ve ever taken, up that point. We spend countless hours in the lab, dissecting animals soaked in formaldehyde until the odor lingers in my hair and my clothes. Some of the students eat sandwiches in the lab, but the smell nauseates me. Norm and I make time one evening to go to a restaurant, something that used to be fun. We choose the Palace, one of our old favorites, and order the usual: a Palace special burger and a baked potato with butter and sour cream with chives. I take a bite of my burger and almost gag. “I can’t eat this,” I say. “Why not?” Norm’s burger is half gone already. He’s a fast, efficient eater. “It tastes like that dogfish shark.” The next week I begin to think of changing majors. But, to what? Norm has switched himself from wildlife biology to pre-vet, and I realize my parents were probably right. I’d have a hard time earning enough money as either an actor or a writer to support him through veterinary school. Plus, Norm’s attitude toward theater or literature as a realistic major mimics those of my parents. My passion for subjects I love isn’t great enough to override my doubts about my talent. I work in an education lab on campus with a friend of mine, Darleen. Sometimes our schedules intersect, as on this day. We are free of students at the moment, just returning some folders to the filing cabinet. We often have free time to study when we’re here. I know she’s majoring in accounting. “What is accounting?” I ask her. Darleen tries to explain it to me. She sighs at my bored expression and pushes a strand of her dark hair behind her ear. I do not understand her explanation, except for one thing. When she graduates in another year, she’ll be able to find a job with a good, steady salary. Enough to put a husband—with the help of a few student loans—through vet school at Ohio State. I make the change. After studying organic chemistry and comparative anatomy, business school is relatively easy for me. I don’t love it exactly, but I don’t hate it either. When I go for my first interview, though, I’m afraid I will hate doing it in the real world. I don’t get the job. Or the next. I’m reminded of my interview for a summer job as a dental hygienist’s assistant. I didn’t get an offer then either. After a few rejections, I decide to be an actor after all. I will act as if being an accountant is exciting… is my dream job, my dream future. Finally, I get a job. A few years later, as an accounting professor, I will apply my acting skills once more, to convince my students that I find the subject matter more stimulating than I actually do. This works for a couple of decades, until I begin to tire of the role. As always, the blame is ultimately mine. As it turns out, I don’t hate being an accountant. And I’m pretty good at it. I’m moving up the ladder in my firm. Granted, much of the time I feel like a fake, likely to be discovered at any moment. But, along the way, I do eventually learn a fair amount. In writing a novel, it’s easy to engage the reader when the protagonist knows exactly what she wants and will do just about anything to achieve the goal. In real life, our motivations aren’t always that straightforward. Yes, we want love and happiness and health. But the trajectory may take a lot of unexpected twists and misdirected efforts. This is also true of the characters in my novels. Acadia, in Song of Sugar Sands, wants Peter to love her, but she does not want to be a preacher’s wife. Sometimes it takes us a while to sort it all out. Sometimes it may take a lifetime. February 2022

As our trip to Maui draws to an end, I reflect on how good I’m feeling now, and how bad I felt when we first arrived. I’d recently purchased some good quality noise-blocking headphones. Since we were flying Southwest from Los Angeles to Maui, we did not have a TV screen on the plane, nor any food except a bag of mixed pretzels and chips and one of brittle chocolate pieces. I think back to the first time we went to Maui. My husband, Norm, had just graduated from veterinary school at Ohio State, and my parents took us and my younger sister to Hawaii as a graduation gift. What a splendid trip it was! We visited four islands: Molokai, Oahu, the big island of Hawaii, and Maui. We fell in love with Maui, so much so that I communicated for a while, after the trip, with a CPA in Maui looking to hire an associate. Though this never panned out, we have returned to the island as often as possible in the years since. I believe this was the first time I flew anywhere, and I could not understand why people complained about airplane food. Back then, everything about the flight was fascinating and delicious. On the current flight, I listened to my book throughout, which was over five hours. During most of that time I wore my noise-blocking headphones, even though I could feel the beginnings of a migraine creeping in. The headphones clamp snugly against the very spots in the sides of my head where pressure sometimes triggers a migraine. Nonetheless, they did a truly great job of blocking out the noise of the plane, so I kept them on. Finally I switched to earbuds, but had to turn the volume on my phone all the way up and still had trouble hearing. On recent flights I’ve started having ear pain on the descent, with my right ear closing up and refusing to pop or open for a few days after the flight. So, I read up on all the tricks, short of having tubes surgically inserted. One is to take antihistamines the day before and every six hours the day of, and possibly the day following the flight. Another is to use a pediatric strength nose spray every five minutes for fifteen minutes (3 or 4 sprays) about an hour before arrival. A third is to purchase special earplugs and insert them about 45 minutes prior to descent. I try to do all three, and it has worked pretty well in the past. But this time we started the descent sooner than I expected. By the time I got my earplugs in and my nose sprayed, we were within thirty minutes of arrival. My ears were aching, and my head pounding by the time we got to our condo, Outrigger, in Napili Shores. I suggested to Norm that next time we fly I should use the computer instead of my phone. He reacted negatively to this suggestion, and I exploded in turn in a way that exacerbated my headache and elevated my blood pressure. Then I felt guilty, which served only to add to the discomfort. The following day—our first full day here—my head hurt all day long. We had a serious ant problem in the bathroom, and we complained to the check-in hostess. She was quite nice, and agreed to call the exterminator company to see how soon they could come out. In the meantime she sent maintenance to our condo to address another issue, a faucet that leaked around the base as soon as we turned it on. I regretted mentioning the latter issue because the maintenance guy wore no mask (this was nearly two years ago, when many workers were still wearing masks), I didn’t know whether he was vaccinated, and he took a long time. Also, he was lying on the floor under the sink next to the toilet, which I needed to use. I also wanted to change into a swimsuit but worried he’d come into the bedroom. Finally, I decided to risk it, change into my swimsuit, and go the lobby bathroom. I took a number of headache remedies, and eventually, late that evening, my headache receded. Nothing makes you appreciate the absence of pain quite so much as coming off a migraine, in my experience. From that point on, we had a great time. Well, one exception. The ocean was colder than I’d hope, and the waves much bigger. The first two times I tried to snorkel I had a panic attack and could barely manage to enter the water with my fins and snorkel. Once in, I was anxious to get out, fearful of crashing into reef or drowning, I’m not sure which. Norm was calm and reassuring, even though he often tells me of his fear of water and I worry as much, or more, about his drowning than about my own. Okay, that’s way too much negativity. So let’s talk about all the positives. Hawaii is truly beautiful. The grounds here are spacious, with gorgeous blooming flowers—huge yellow hibiscus with deep red centers, little clusters of yellow blossoms, and white plumeria edged in pink lace; green and white striped and red-leafed plants; tall, lanky palm trees, everywhere you turn. There are two pools. One has a pair of whales painted on the bottom, the other Hawaiian flowers. Both are mildly heated this time of year. I prefer the one with the whales design, a hot tub, and plenty of umbrellas. The other is next to the Gazebo Restaurant, open from 7:30 AM to 2:00 PM and known for their banana macadamia nut pancakes, topped with whipped cream and coconut syrup. The lines are almost always long, but we’ve learned you can call in your order, pick it up, and eat on your own patio looking out at the ocean. We’ve done this almost every morning except the first, when we ate in the restaurant in the lobby. On the second or third day, we walked to the grocery, where we purchased yogurt, bagels, avocado, cheese, sparkling water, coconut bread, and papaya. We did not rent a car, but remembered from our last time here that, in addition to the Gazebo and the lobby restaurant, there’s a great upscale restaurant nearby. We went to the Sea House twice this time, once for Happy Hour small plates (ribs, ahi nachos, seared ahi, and tiramisu) and once, with reservations, for dinner. The highlight of the dinner for me was the starry walk to and from the restaurant. I haven’t seen such bright stars since we were on the south island of New Zealand. The sky was ablaze. Norm had crab-breaded monchong with lobster sauce, and I had a trio of lobster, scallops, and fish with furikake. Coconut bread pudding for dessert with vanilla ice cream, yummy. The restaurants are asking for vaccination cards, and we wore masks entering and exiting though not everyone does. It’s hard to imagine that this brief period of masking accomplishes much since you have to remove them to eat or drink. I did much better today with the snorkeling. We walked farther, to the south side of the bay, where the water was calmer. We went in around 3 PM, about a half hour after low tide. Visibility was not great initially, but improved. We saw a few needle-nose fish, red and black sea urchins, yellow banner fish, schools of fish with a single yellow stripe, lots of black fish with cute yellow or orange bowties near the tail, and many more. No turtles on this trip. Sitting on the shore, we spotted lots of humpback whales breaching, blowing, jumping, and generally frolicking. A couple of times we glimpsed the black tail clearly as they dove. Orange and yellow butterflies fluttered near us, and Brazilian cardinals, sparrows, doves, and white cattle egrets darted about and called to one another. I spoke with an attractive sixty-year-old woman in the hot tub, Lorraine, who recommended a whale watching dinner cruise. I couldn’t tell whether her unusually long eyelashes were real or fake. I hated to think what I must look like, having just come from snorkeling with my hair plastered down my face and head. I felt we were kindred spirits, to use L.M. Montgomery’s words. She said her husband was content to idle, but she wanted to be busy. She is authoring a textbook on education while she’s here, and contemplating retirement. She works as an education consultant, and plans to move toward 50% this year, 30% the next, and so on. Seems a good plan to me. Going from 100% to zero, as I did at Vanderbilt, can be a tough adjustment, especially if you’re a person who thrives on a full schedule. As we sat there chatting in the deliciously warm water, a teenage girl approached. “I need to get the key,” she said. Lorraine found it for her and returned to the hot tub. I must have looked surprised, for she told me, “There are actually nine of us staying in a one-bedroom condo.” I had supposed she and her husband were there alone, given to vacationing in places like Maui. I have often chosen budget stays over the years, so as to maximize my travel ventures rather than opting for more extravagant but fewer trips. I remember staying in hotel rooms with two double beds when my kids were young, somehow accommodating the four of us plus my parents. Another day at the hot tub, a group of teenage Hawaiian boys turned up to play ball in the adjacent swimming pool. A deeply tanned, gray-haired man seated near me remarked, “Must be pool hopping day.” “What’s that?” I asked. “They are locals. When I was their age, we used to go from one resort to another…until we’d get thrown out. You didn’t think they were staying here, did you?” “I guess I did.” I am not entirely innocent of this vice myself, though I never knew what it was called. For instance, we often stay in a small hotel in Fort Lauderdale, next door to a larger hotel with a lazy river. I’ve been known to slip into their lazy river, and was once asked to leave. Lorraine had gone on the Hula Girl cruise, so I called them. Unfortunately, they had canceled the cruise for Saturday, our last and only available evening. My note to myself is to plan ahead better next time. Our ants have returned off and on; but, apart from one dream, they are no longer worrying me. In fact, I feel sorry for them. They seem so directionless, staggering around, with no clear purpose, rather like a new retiree. I wish they’d find another place to hang out. Tonight we ate at the lobby restaurant. Not long before the trip, I went shopping for the first time in a while. Quite by accident, I found a rack of bargain dresses in the Soma shop, when I was looking for a new nightgown to replace the two I wear all the time. One of them is a Hawaiian-looking black sundress with white flowers. I wore it to dinner tonight. I had the ahi poke bowl, and Norm had mahi mahi with a lovely lemon caper butter sauce. We walked to the beach afterward to look at the sky around sunset. The clouds partially covered Molokai, and the stars and planets were just beginning to come out. Yesterday, though it didn’t rain, we had a lovely rainbow around the time we left the pool. After watching some basketball on TV (3rd ranked UCLA vs. Arizona State, three overtimes, victory to Arizona State), we went back outside to look at the stars. Amazing! Norm has an app called Sky View on his phone, telling us we were both confused about the Big Dipper. And we thought that was the most obvious one…so much for our knowledge of stars. That does not hinder my enjoyment of them. As a final point, I think that stopping off for a few nights in Los Angeles helps me adjust quickly to the time difference. We have always made a habit of this, because one or both of our kids has lived in LA for many years. But, even if you don't have family there, I think a night or two in LA is worth doing. There’s a two-hour difference between Tennessee and Los Angeles, and another two hours between Los Angeles and Hawaii. One of my friends says we should impose a rule on how long we can discuss health issues when we talk. The older I get, the more I see the wisdom of such a rule. No one really likes to hear another person drone on and on about their aches and pains. So, when I catch myself doing this, I’m reminded uncomfortably of my grandmother’s neighbor, Mrs. Oglesby, and I try to change the subject.

My grandmother, Meme, insisted I visit Mrs. Oglesby regularly. “How are you doing?” I’d ask. “Not well. Not well at all.” And she’d launch into a litany of complaints. As I listened and commiserated, I’d vow never to become so negative. This past year was particularly challenging. It all started one day at the beach when I was boogie boarding like a kid instead of the past-middle-age citizen I am. My right knee began to trouble me, but the waves were so enticing, I ignored the pain, assuming it would be gone on the morrow. It was not. When I visited the sports doctor, he predicted a torn meniscus and ordered an MRI. When the torn meniscus turned out to be on the opposite side from the pain, I should have been wary. Instead I followed his recommendation to see a surgeon, who suggested a surgery called a partial meniscectomy. “A chance to cut is a chance to cure,” my husband, a retired veterinarian, always jokes. “That’s the surgeon’s motto.” He did a lot of surgeries himself, and I know he didn’t abide by this motto, not when he thought another approach worked well. I’m writing about this largely because I’d like to caution anyone considering this surgery to think more carefully than I did before leaping in. While I was recovering from the surgery, I made my second mistake. I became overly zealous with the exercises recommended by my physical therapist and strained my opposite hip. With pain in both my right knee and my left hip, walking and exercising became challenging in a totally new and not very pleasant way. Now for mistake three. We were scheduled for a tour of Costa Rica, but had not purchased travel insurance. Because the pain was pretty severe and I knew the trip involved a fair amount of hiking, I looked into the cancellation options. They were not appealing, so we decided to go ahead with the trip. During the hikes, the pain in my left hip was so intense, I shifted far too much weight to my still-recovering right leg. Result? Now the other meniscus in my right knee has indeed torn. Another surgery? I don’t think so. Not unless it’s a total knee replacement, but am I ready for that? By the way, Costa Rica is beautiful, but that’s a subject for another blog. The surgeon who performed my partial meniscectomy told me he saw very little osteoarthritis in my right knee at that time. Unfortunately, one of the side effects of a partial meniscectomy is an increased risk of osteoarthritis in the future. But so soon? It had only been a few months. At this point I decided rest was my best friend. The less I exercised, walked, or climbed stairs, the better both my hip and knee felt. I’ve lost count…is this mistake number four or five? My fit bit informed me that some days my step count didn’t even reach one thousand, and my exercise minutes were often zero. But my hip and knee were feeling better. Next problem? After my annual physical, my primary physician ordered blood work, and we discovered my “bad” cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglycerides had increased significantly. Could this be due to a lack of exercise? We still don’t know, but it’s been about a year now since that lovely day on the beach when the boogie boarding waves proved irresistible. Because I’m back at the beach this week, longing to be on my boogie board once more, the year’s events have come flooding back. But I’m realizing I’ve done what my friend advised against. I’ve spent way too much time and space discussing health issues. So, I’ll stop whining for now. Take-away message? Count your blessings on your good days, exercise even if it hurts a little, and think twice before getting a partial meniscectomy on your knee. One of the most beloved characters in my fiction is the grandmother in The Ticket, who always puts a positive face on the bleakest of circumstances. As the apostle Paul challenged, “Rejoice always… in everything give thanks.” Let’s not allow a little discomfort to spoil the joys of life—like children, grandchildren, beaches, reading, and, yes, if you feel so inclined, even boogie boarding. Mine was the last toast. The preceding ones were great, full of emotion and kind words. I thought I’d go for a touch of humor.

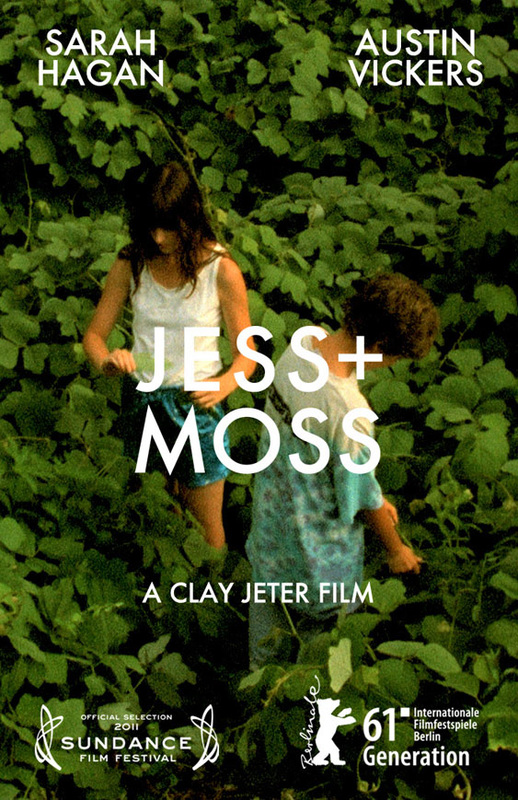

I daresay I’ve known Clay longer than anyone here. His dad and his sister come close, of course, but I knew him in the womb. Even then he was difficult, always kicking as if he wanted to get the show on the road. Then, when I decided I was ready—after all, his sister had been almost three weeks early—he decided to wait for the due date. He’s always struggled a bit with decisions, as do I. We think and analyze. Then we rethink and reanalyze. Was he doing all this in the womb? Skipping ahead to age five…I got a ping pong table for my birthday that year. You could reposition the table from a two-person table to a one-person backboard if you knew how. We instructed Clay and his sister not to try this without adult supervision. However, we did not instruct Clay’s friend Michael. I’m not saying Clay was a tattle tale, but he was a reporter. He came flying up the stairs. “Michael broke my favorite table!” he said. “Where is Michael?” “I don’t know.” Michael had fled the scene. On the following day, the phone rang, and Clay answered. His end of the conversation went something like this. “Hello? Michael?” “Who? Who is this? Jay?” Clay put the phone down and turned to us. “Bust my butt, he’s changed his name.” He sighed as he picked the phone back up. “I’m never going to remember this,” he muttered. Then, into the phone, he said, “Hello? Jay?” Over the next few months, Clay and I played a lot of ping pong. He was too short to reach a lot of shots, so we moved a couch to his side of the table. He ran back and forth, and he became quite good. He always wanted to keep score and play to 21. However, if he didn’t like the way a point went down, he’d call out. “Do over!” Consequently, after about an hour the score might be 4 to 3. Clay wasn’t content just to win the point. Oh, no, he needed a good rally and the ball to go more or less where he intended. “Disallowed!” he’d announce. “At this rate, we’ll be here until midnight,” I often complained. Finally Clay would begin to tire. “I think the score must be 18 to 17 now,” he’d say. When Clay was six [a few good-natured groans from my audience at this point] we threw a party for his sister’s tenth birthday at a hotel with a swimming pool. Clay, as usual, wore his water wings, or floaties. My dad was convinced it was time Clay swam without the aid. He suggested, he encouraged, and finally he tried to shame Clay. “You don’t want the big kids at school making fun of you, do you?” (By the way, my dad and mom just left before the toasts, but they were here for the wedding. They’ve been married seventy-two years.) “I don’t care,” Clay said. “One of these days, I’ll be a grown-up daddy with kids of my own, and I’ll still be wearing my floaties.” Less than a year later, his sister had taught him to swim, and soon he was doing backward flips and dives into the pool. Clay loved sports of all kinds from an early age. He played tee-ball and then baseball, basketball, soccer, and tennis. He loved being part of a team. He was very patient and supportive of his teammates. Not so much, though, of himself. When he messed up—for example, failing to strike out the batter in baseball—he took it too much to heart. He gave up baseball soon after, but continued to enjoy the other sports for several years. Still does, I think, and loves watching baseball. At age nine, he had an opportunity for an audition in Townsend, Tennessee. Unfortunately, it was the same day as a soccer match. This was around the same time he had proclaimed, “Soccer is my life.” “Can’t I do both?” he asked. I shook my head. “They’ve already seen you on tape. Now the director and producers want to meet you in person.” Tough decision. After much deliberation, he went to the audition. By the time he was eleven, he’d done a television series, a few commercials, and a movie or two. We decided to go to Los Angeles for pilot season. His dad was working back in Tennessee, so it was up to me to navigate LA traffic. Problem was I had (and have) absolutely no sense of direction. North, south, east, and west are meaningless to me; I think in terms of right or left. And there was no GPS back then. I would drive, and Clay would direct me, using a paper map. “You’re going to need to go to the right up here. You can change lanes now,” he’d say. I trusted him. But, from time to time, he’d fall asleep at the job. When I could see the roads splitting up ahead, I’d try to rouse him. “Clay! Clay! Wake up! Which way do I go?” Eventually, he’d lift his head and mumble a direction, then fall back to sleep. Half an hour later or so, he’d rouse. “Where are we?” he’d ask. “You told me to go this way,” I’d say. “Oh, Mom, what have you done?” Perhaps I should have suspected even then that his future might lie in this city, where the traffic terrified me so much more than him. Still, I clung to the belief that after film school at U.S.C., he’d probably return to Tennessee—if not immediately, in a few years, surely. Then he met Sarah. As I looked around at the wedding guests, our family was vastly outnumbered by Sarah’s. “We may not be as numerous as the Hagans,” I said. “But we’re loud. You can hear us coming. And we say what we think.” When we met Sarah, we all said to one another, “I like her.” “I like her.” “I really like her.” We also said, “How in the world did he manage to find someone who is more like Clay than Clay himself?” They are both perfectionists, with immense patience for artistic endeavors and meticulous attention to detail. They keep on striving for perfection, long after Clay’s dad, his sister, and I are saying, “Come on. That’s good enough. Be done with it, and move on to something else.” When Nikki was in elementary school and had to make a poster, she’d get it done in a hurry. If she messed up a little, she’d just write over that letter with the correct one. When Clay made a poster, he’d measure carefully the space between each and every letter. Then, if he messed up, he’d need a do-over. Throw that one away, and start fresh. If I had to pick one quality that most impresses me about Clay and Sarah as a couple, it’s how supportive—and patient—they are of each other. This next part is an addendum. I didn’t say it at the wedding, but I should have. Clay, your dad always claims you got your brains, your competitiveness, and your artistic inclination from me. I should say you get your heart—big as Alaska, your generous nature, your humility, and your powers of observation from him. And your sense of direction. Your sister always says you’re my favorite child. But that’s only half true. You’re both my favorites. A toast… to Clay and Sarah… and a long, happy life together. I love you so much it hurts. “I just don’t think those current hairstyles are becoming on anyone,” my mom often says. To prove her point, she’s maintained more-or-less the same bubble haircut over the past, oh, fifty years or so.

I never agree with her out loud. Indeed, I do usually think the current hairstyles look fine on most people other than myself. Young, fresh-faced news commentators, actresses on my mom’s “stories,” and the younger generation of women at church wear these styles with aplomb. When I look in the mirror, however, I’m beginning to agree with my mother. Would I look better if I reverted to one of my older styles? Or were they becoming only because my face was once younger, fresher? I don’t think about this question too often, mainly on days when I’ve scheduled a haircut and need to tell the stylist what I want. This year, though, my son has planned a big wedding event and invited a lot of his California friends and fiancée’s family members I’ll be meeting for the first time. Staring at myself in the mirror, I ponder the question. Should I follow my mom’s habit and revert to an old hairstyle, or ignore my face and be more contemporary? And does it really matter? Ah, the vanity, the vanity. In my novel, Joy After Noon, Joy worries that she’s being compared unfavorably to Ray’s first wife, now deceased. Joy After Noon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B08TL79RPJ Who among us doesn’t suffer the occasional pangs of self-doubt, whether they are about our weight, our face, our hair, our social skills, or our cooking? Only God ignores the outer shell and focuses on our inner being. Let us strive to keep it young and fresh. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed