|

Mine was the last toast. The preceding ones were great, full of emotion and kind words. I thought I’d go for a touch of humor.

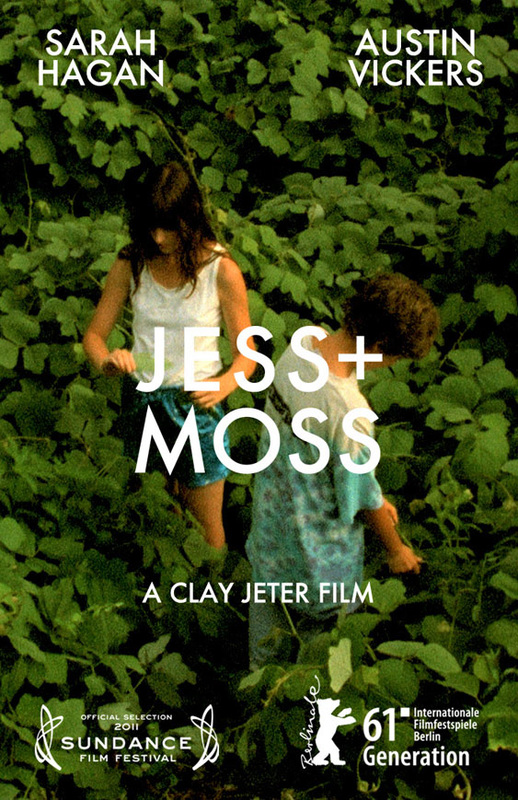

I daresay I’ve known Clay longer than anyone here. His dad and his sister come close, of course, but I knew him in the womb. Even then he was difficult, always kicking as if he wanted to get the show on the road. Then, when I decided I was ready—after all, his sister had been almost three weeks early—he decided to wait for the due date. He’s always struggled a bit with decisions, as do I. We think and analyze. Then we rethink and reanalyze. Was he doing all this in the womb? Skipping ahead to age five…I got a ping pong table for my birthday that year. You could reposition the table from a two-person table to a one-person backboard if you knew how. We instructed Clay and his sister not to try this without adult supervision. However, we did not instruct Clay’s friend Michael. I’m not saying Clay was a tattle tale, but he was a reporter. He came flying up the stairs. “Michael broke my favorite table!” he said. “Where is Michael?” “I don’t know.” Michael had fled the scene. On the following day, the phone rang, and Clay answered. His end of the conversation went something like this. “Hello? Michael?” “Who? Who is this? Jay?” Clay put the phone down and turned to us. “Bust my butt, he’s changed his name.” He sighed as he picked the phone back up. “I’m never going to remember this,” he muttered. Then, into the phone, he said, “Hello? Jay?” Over the next few months, Clay and I played a lot of ping pong. He was too short to reach a lot of shots, so we moved a couch to his side of the table. He ran back and forth, and he became quite good. He always wanted to keep score and play to 21. However, if he didn’t like the way a point went down, he’d call out. “Do over!” Consequently, after about an hour the score might be 4 to 3. Clay wasn’t content just to win the point. Oh, no, he needed a good rally and the ball to go more or less where he intended. “Disallowed!” he’d announce. “At this rate, we’ll be here until midnight,” I often complained. Finally Clay would begin to tire. “I think the score must be 18 to 17 now,” he’d say. When Clay was six [a few good-natured groans from my audience at this point] we threw a party for his sister’s tenth birthday at a hotel with a swimming pool. Clay, as usual, wore his water wings, or floaties. My dad was convinced it was time Clay swam without the aid. He suggested, he encouraged, and finally he tried to shame Clay. “You don’t want the big kids at school making fun of you, do you?” (By the way, my dad and mom just left before the toasts, but they were here for the wedding. They’ve been married seventy-two years.) “I don’t care,” Clay said. “One of these days, I’ll be a grown-up daddy with kids of my own, and I’ll still be wearing my floaties.” Less than a year later, his sister had taught him to swim, and soon he was doing backward flips and dives into the pool. Clay loved sports of all kinds from an early age. He played tee-ball and then baseball, basketball, soccer, and tennis. He loved being part of a team. He was very patient and supportive of his teammates. Not so much, though, of himself. When he messed up—for example, failing to strike out the batter in baseball—he took it too much to heart. He gave up baseball soon after, but continued to enjoy the other sports for several years. Still does, I think, and loves watching baseball. At age nine, he had an opportunity for an audition in Townsend, Tennessee. Unfortunately, it was the same day as a soccer match. This was around the same time he had proclaimed, “Soccer is my life.” “Can’t I do both?” he asked. I shook my head. “They’ve already seen you on tape. Now the director and producers want to meet you in person.” Tough decision. After much deliberation, he went to the audition. By the time he was eleven, he’d done a television series, a few commercials, and a movie or two. We decided to go to Los Angeles for pilot season. His dad was working back in Tennessee, so it was up to me to navigate LA traffic. Problem was I had (and have) absolutely no sense of direction. North, south, east, and west are meaningless to me; I think in terms of right or left. And there was no GPS back then. I would drive, and Clay would direct me, using a paper map. “You’re going to need to go to the right up here. You can change lanes now,” he’d say. I trusted him. But, from time to time, he’d fall asleep at the job. When I could see the roads splitting up ahead, I’d try to rouse him. “Clay! Clay! Wake up! Which way do I go?” Eventually, he’d lift his head and mumble a direction, then fall back to sleep. Half an hour later or so, he’d rouse. “Where are we?” he’d ask. “You told me to go this way,” I’d say. “Oh, Mom, what have you done?” Perhaps I should have suspected even then that his future might lie in this city, where the traffic terrified me so much more than him. Still, I clung to the belief that after film school at U.S.C., he’d probably return to Tennessee—if not immediately, in a few years, surely. Then he met Sarah. As I looked around at the wedding guests, our family was vastly outnumbered by Sarah’s. “We may not be as numerous as the Hagans,” I said. “But we’re loud. You can hear us coming. And we say what we think.” When we met Sarah, we all said to one another, “I like her.” “I like her.” “I really like her.” We also said, “How in the world did he manage to find someone who is more like Clay than Clay himself?” They are both perfectionists, with immense patience for artistic endeavors and meticulous attention to detail. They keep on striving for perfection, long after Clay’s dad, his sister, and I are saying, “Come on. That’s good enough. Be done with it, and move on to something else.” When Nikki was in elementary school and had to make a poster, she’d get it done in a hurry. If she messed up a little, she’d just write over that letter with the correct one. When Clay made a poster, he’d measure carefully the space between each and every letter. Then, if he messed up, he’d need a do-over. Throw that one away, and start fresh. If I had to pick one quality that most impresses me about Clay and Sarah as a couple, it’s how supportive—and patient—they are of each other. This next part is an addendum. I didn’t say it at the wedding, but I should have. Clay, your dad always claims you got your brains, your competitiveness, and your artistic inclination from me. I should say you get your heart—big as Alaska, your generous nature, your humility, and your powers of observation from him. And your sense of direction. Your sister always says you’re my favorite child. But that’s only half true. You’re both my favorites. A toast… to Clay and Sarah… and a long, happy life together. I love you so much it hurts.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed